X-29 aircraft

Control systems make other systems do what we want them to do, without us having to do all the work. Examples of control systems in everyday life include the thermostat that regulates the temperature of a room and the cruise control that regulates the speed of a car. Typically, the core of a control system is an algorithm that computes the signal that must be applied at the input of a system so that its output follows certain reference values. Practical implementation involves a computer, a sensor (or sensors) that measures the output of the system, and an actuator (or actuators) that applies the required actions to the system. The actions may be physical forces, electrical signals, chemical products, or any other variables that affect the state of the system. To become an expert in control, you should be comfortable with mathematics and computing. You should also be curious enough to study closely a variety of engineering applications.

Two modern applications of control theory are flight control and active noise control. In the X-29 aircraft shown below, the dynamic behavior is so unstable that a human pilot is unable to maintain steady flight without the feedback actions implemented by a flight control computer. In the worst flight condition of the X-29, an angular deviation from horizontal flight doubles every 0.12 seconds (the stabilization task is equivalent to the one required to balance a 17.4 inch stick on a finger). Computations are performed 40 times per second to provide adequate stabilization and control of the aircraft.

X-29 aircraft |

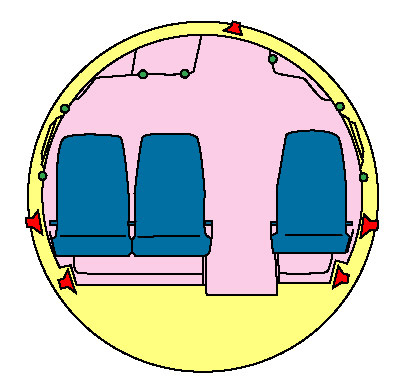

The figure below shows an active noise control system for a turboprop aircraft. Here, the purpose of the control system is to reduce the noise in the cabin of the aircraft. The result is achieved by measuring the sound with microphones (shown in green) and generating cancelling sound waves using speakers (shown in red). The SAAB 2000 aircraft has 72 microphones and 36 speakers, so that the computer must deal with a large number of sensors and actuators. The control problem is quite different from the flight control application. There is no issue of stabilization of the system or of tracking of commands. The problem is purely one of disturbance rejection. In both cases, the control engineer designs the algorithm that is coded in the control computer so that the desired results are achieved.

Active noise control system |

| Professor Marc Bodson | Email: marc.bodson@utah.edu | Prof. Bodson's web page |

| Professor Mingxi Liu | Email: mingxi.liu@utah.edu | Prof. Liu's web page |

| Professor Arn Stolp | Email: arnstolp@ece.utah.edu | Prof. Stolp's web page |

| Professor Jacob A. George | Email: jake.george@utah.edu | Prof. George's web page |

| ECE 5960/6960 | Convex Optimization (Fall) |